Stimate razesu, cum crezi din ce cauză istoricii români și statul românesc falsifică documentele istorice? Cine dorește ca națiunea să-și uite adevărata sa origine străveche? Cine sunt aceste forțe? și cine stă în spatele lor?

-istoricii romani au incercat sa faca ceea ce au facut totii istoricii din Europa care au incercat sa puna bazele si sa cuaguleze in jurul unor valori, o natiune...un simplu exemplu la anul 1789 jumatate din populatia Frantei nu vorbea franceza......

-personal eu sint adeptul teoriei admigratiei...formarea poporului roman la sudul Dunariii...pentru ca orice a-ti spune voi limba romana este o limba latina in sintaxa sa..pentru cei care stiu ce inseamna sintaxa unei limbi....

-uite in linii mari ce se stie despre limba daca...

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dacian

Spoken in

Romania,

Moldova, parts of

Ukraine,

Hungary,

Serbia, and Northern

Bulgaria

Date of extinction

probably by the sixth century AD

Language family

Indo-European

Language codes

ISO 639-3

xdc

Indo-European topics

Indo-European languages (

list)

Albanian · Armenian · BalticCeltic · Germanic · GreekIndo-Iranian (

Indo-Aryan,

Iranian)

Italic · Slavic

extinct: Anatolian · Paleo-Balkan (Dacian,

Phrygian, Thracian) · Tocharian

Proto-Indo-European language

Vocabulary · Phonology · Sound laws · Ablaut · Root · Noun · Verb

Indo-European language-speaking peoples

Europe:

Balts · Slavs · Albanians · Italics · Celts · Germanic peoples · Greeks · Paleo-Balkans (

Illyrians · Thracians · Dacians)

·

Asia: Anatolians (Hittites, Luwians) · Armenians · Indo-Iranians (Iranians · Indo-Aryans) · Tocharians

Proto-Indo-Europeans

Homeland · Society · Religion

Indo-European archaeology

Abashevo culture · Afanasevo culture · Andronovo culture · Baden culture · Beaker culture · Catacomb culture · Cernavodă culture · Chasséen culture · Chernoles culture · Corded Ware culture · Cucuteni-Trypillian culture · Dnieper-Donets culture · Gumelniţa-Karanovo culture · Gushi culture · Karasuk culture · Kemi Oba culture · Khvalynsk culture · Kura-Araxes culture · Lusatian culture · Maykop culture · Middle Dnieper culture · Narva culture · Novotitorovka culture · Poltavka culture · Potapovka culture · Samara culture · Seroglazovo culture · Sredny Stog culture · Srubna culture · Terramare culture · Usatovo culture · Vučedol culture · Yamna culture

Indo-European studies

The Dacian language was spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient regions of Dacia, Moesia and possibly some surrounding regions. It belonged to the Indo-European language family.[1] As far as can be ascertained from the scarce available evidence, the Dacian language belongs to the satem group of the Indo-European languages.[2][3]

Dacian is considered by some scholars e.g. Baldi (1983) and Trask (2000), to be a dialect of the same language as Thracian; or a separate language from Thracian but related to it[1] and to Phrygian;[4] or a language unrelated to either Thracian or Phrygian (except in the distant sense of sharing an Indo-European origin) e.g. Georgiev (1977). [5] The label Daco-Thracian (or Thraco-Dacian) is applied by linguists who see Dacian as a northern variety of Thracian.[6]

The Dacian language is poorly documented. Unlike for ancient Thracian, or Phrygian, only one Dacian inscription is known to have survived.[7][8] In ancient literary sources, the Dacian names for a number of medicinal plants and herbs survive in ancient texts[9][10] that includes about 60 plants names with Dioscorides.[11] Dacian language is also known through about 1,150 proper names[8][12]), about 900 toponyms.[8] Finally, there are few hundred words in modern Albanian and Romanian languages, which have been suggested to originate in ancient Balkan languages such as Dacian (see List of Romanian words of possible Dacian origin).

[edit] Origin

There is scholarly consensus that Dacian was a member of the Indo-European family of languages. These descended, according to the two leading theories of the expansion of IE languages, from a proto-Indo European tongue that originated in an urheimat ("original homeland") in S. Russia/ Caucasus region, (Kurgan hypothesis) or in central Anatolia (Anatolian hypothesis). According to both theories, proto-IE reached the Carpathian region not later than ca. 2,500 BC.[13][14] Supporters of both theories have suggested this region as IE's secondary urheimat, in which began the differentiation of proto-IE into the various European language-groups (e.g. Italic, Germanic, Balto-Slavic, Celtic). In the Bronze Age, proto-Thracian populations emerged from the fusion of the local Eneolithic (Chalcolithic) stock with the intruders of the transitional Indo-Europeanization Period.[15][16] From these proto-Thracians, in the Iron Age, there were developed the Dacians / North Thracians of the Danubian-Carpathian Area on the one hand and the Thracians of the eastern Balkan Peninsula on the other.[15][16] It is thus generally agreed that Dacian developed in the Carpathian region probably during the 3rd millennium BC, although by which evolutionary pathways remains uncertain. According to Georgiev, the Dacian language was spread to South of the Danube by tribes from Carpathia penetrating the central Balkans in the period 2,000-1,000 BC, with further movements (e.g. the Triballi tribe) after 1,000 BC, until ca. 300 BC.[17] According to ancient sources, i.e. Strabo, Daco-Moesian was further spread into Asia Minor, in the form of Mysian, by a migration of the Moesi people (Strabo asserts that Moesi and Mysi were variants of the same name).[18]

[edit] Sources

Many characteristics of the Dacian language are disputed or unknown. No lengthy texts in Dacian or Thracian exist. Surviving evidence for the language is limited to very few brief and imperfectly understood inscriptions, glosses in Greek and Latin writers and proper names occurring in Greek or Latin texts and inscriptions. Of the five known inscriptions claimed as Thracian or Dacian (one on a tombstone, the others on rings or pots) four are in Greek script and from Bulgaria, and are therefore Thracian in the narrow sense of the word and one is in Latin script, and from Romania, and so Dacian.[19] No lengthy Dacian inscriptions survive, save names using the Latin and Greek alphabet. What is known about the language derives from:

Dacian gold currency minted with the inscription

ΚΟΣΩΝ using Greek letters. Found in

Transylvania, Romania.

- Toponyms, hydronyms, and proper names (including the names of kings).

- The Dacian names of about fifty plants written in Greek and Roman sources (see List of Dacian plant names). Etymologies have been established for only a few of them.[20]

- Substratum words found in Romanian, the language that is spoken in most of the places where Dacians lived. These include about 400 words of uncertain origin (such as brânză 'cheese' and balaur 'dragon'). About 160 of these words have cognates in Albanian.

- In 1st century AD, the Roman poet Ovid claimed that he learned the language of the Getae after being exiled to Tomis (today Constanţa) in Dacia. In his Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto he claimed to have composed poems in the language: Getico scripsi libellum sermone ‘I have written a book in the Getic language’.[19] If this is true, they have not been preserved.

[edit] Geographical extent and linguistic area (Chronologically)

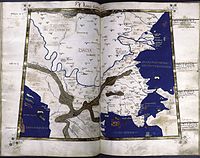

Celtic, Illyrian and Dacian languages 4th - 3rd century BC

Map of

Dacia 1st century BC

[edit] Linguistic area

Probably Dacian used to be one of the major languages of South-Eastern Europe, spoken from what is now Eastern Hungary to the Black Sea shore. According to historians, as a result of the linguistic unity of the Getae and Dacians that result from the record of ancient writers Strabo, Cassius Dio, Trogus Pompeius, Appian and Pliny the Elder, contemporary historiography often uses the term Geto-Dacians to refer to the people living in the area between the Carpathians, the Haemus (Balkan) Mountains and the Black Sea. Strabo gave the more specific information recording that “the Dacians speak the same language as the Getae” a dialect of the Thracian language.[21] The information provided by the Greek geographer was completed by other literary, linguistic, and archeological evidence. According to these, the Geto-Dacians occupied the territory in the west and northwest as far as Moravia and the middle Danube , to the area of present-day Serbia in the southwest, and as far as the Haemus Mountains in the south. The eastern limit of the territory inhabited by the Geto-Dacians was formed by the shore of the Black Sea and the Tyras River, at times reaching as far as the Bug River, the northern limit reached the Trans-Carpathian Ukraine and southern Poland.[22]

Over time, some peripheral areas of the Geto-Dacians territories were affected by the presence of other people, such as the Celts in the west, the Illyrians in the southwest, the Greeks and Scythians in the east, and the Bastarns in the northeast. Nevertheless, between the Tisa River, the Haemus Mountains, the Black Sea, the Dniester River, and the northern Carpathians, a continuous Geto- Dacian presence was maintained.[23]

According to Bulgarian linguist Georgiev, the Daco-Mysian region included Dacia (approximately contemporary Romania and Hungary to the east of the Tisza River, Mysia (Moesia) and Scythia Minor (contemporary Dobrogea).[24]

[edit] Chronology

[edit] 1st century BC

In 53 BC, Julius Caesar stated that the lands of the Dacians started on the eastern edge of the Hercynian Forest.[25] This corresponds to the period between 82-44 BCE, when the Dacian state reached its widest extent during the reign of king Burebista : in the West it probably extended as far as the middle Danube River valley (present-day Hungary), in the East and North to the Carpathians (in Slovakia) and in the South to the lower Dniester valley (southwestern Ukraine) and western coast of the Black Sea as far as Appollonia.[26] At that time, the Dacians built a series of hill-forts at Zemplin (Slovakia), Mala Kopania(Ukraine), Onceşti, Maramureş (Romania) and Solotvyno (Ukraine).[26] The Zemplin settlement appears to belong to a Celto-Dacian horizon, as well as the river Patissus (Tisza)'s region, including its upper stretch, according to Shchukin (1989).[27] According to Parducz (1956) Foltiny (1966), Dacian archaeological finds extend to the West of Dacia, occurring along both banks of the Tisza.[28] Besides the possible incorporation of a part of Slovakia into the Dacian state of Burebista, there was also Geto-Dacian penetration of south-eastern Poland, according to Mielczarek (1989).[29] Polish linguist Milewski Tadeusz (1966 and 1969) noted that in Southern regions of Poland we meet names unknown in the North Poland, related to the Dacian and Illyrian names.[30][31] On the grounds of these names it may be said that the region of the Carpathian and Tatra Mountains was inhabited by Dacian tribes linguistically related to ancestors of nowadays Albanians.[32][31]

Also, a formal statement by Pliny indicated the river Vistula as the western boundary of Dacia, according to Nicolet (1991).[33] The section between the Prut and the Dniester the northern extent of the appearance of Geto-Dacian elements in the 4th century BC coincides roughly with the extent of present-day the Republic of Moldova.[34]

According to Müllenhoff (1856) Shütte (1917) Urbannczyk (2001) Matei-Popescu (2007) Agrippa’s commentaries mention Vistula river as the western boundary of Dacia.[35][36][37][38] Urbannczyk (1997) speculates that according to Agrippa’s commentaries along with the map of Agrippa (before 12 BC) Vistula river separated Germania and Dacia.[39] Map is lost and its contents are unknown (See one possible reconstruction: [1] )[Full citation needed] However, later Roman geographers, including Ptolemy (AD 90 – c. AD 168) (II.10, III.7) and Tacitus (AD 56 – AD 117) (ref: Germania XLVI) considered the Vistula as the boundary between Germania and Sarmatia Europaea, or Germania and Scythia.[35].

[edit] 1st century AD

Around 20 AD, Strabo wrote Geographica [40] that provides information regarding to the extent of regions inhabited by Dacians. On its basis, Lengyel and Radan (1980), Hoddinott (1981) and Mountain (1998) consider that the Geto-Dacians inhabited both sides of the Tisza river prior to the rise of the Celtic Boii and again after the latter were defeated by the Dacians.[41][42][43][44] The hold of the Dacians between Danube and Tisza appears to have been only loose.[45] However, the Hungarian archaeologist Parducz (1856) argued a Dacian presence west of the Tisza dating from the time of Burebista (Ehrich 1970).[28] According to Tacitus (AD 56 – AD 117) Dacians were bordering Germany in the south-east while Sarmatians bordered it in the east.[46]

In the 1st century AD, the Iazyges settled West of Dacia, on the plain between the Danube and the Tisza rivers, according to some scholars' interpretation of Pliny's text: “The higher parts between the Danube and the Hercynian Forest (Black Forest) as far as the winter quarters of Pannonia at Carnutum and the plains and level country of the German frontiers there are occupied by the Sarmatian Iazyges, while the Dacians whom they have driven out hold the mountains and forests as far as the river Theiss”.[47] [48][49] [50][51] Archaeological sources indicate that the local Celto-Dacian population retained its specificity as late as the third century.[34] Archaeological finds dated to the 2nd c. AD, after Roman conquest, indicate that during that period and vessels found in some of the so-called Iazygian cemetery reveal fairly strong Dacian influence (Mocsy 1974).[52] M. Párducz (1956) and Z. Visy (1971) reported a concentration of Dacian finds in the Cris-Mures-Tisza region and in the Danube bend area (around Budapest). These maps of findings remain valid today, but they had been completed with additional findings that cover a wider area, particularly the interfluve area between the Danube and Tisza (Toma 2007). [53] However, this interpretation has been invalidated by late 20th-century archaeology, which has discovered Sarmatian settlements and burial sites all over the Hungarian Plain, on both sides of the Tisza e.g. Gyoma (SE Hungary) , Nyiregyhaza (NE Hungary).[Full citation needed] The Barrington Atlas shows Iazyges occupying both sides of Tisza (map 20).

[edit] 2nd century AD

Written a few decades after the Roman conquest of Dacia 105-106 AD[54], Ptolemy's Geographia included boundaries of Dacia. According to some scholars' interpretation of Ptolemy (Hrushevskyi 1997, Bunbury 1879, Mocsy 1974, Barbulescu and Nagler 2005) Dacia was the region between the rivers Tisza, Danube, upper Dniester, and Siret.[55][56] [57][58] The mainstream of historians accepted this interpretation: Avery (1972) Berenger (1994) Fol (1996) Mountain (1998), Waldman Mason (2006).[59][25][60][61][62] Ptolemy also provided Dacian toponyms in the Upper Vistula (Polish: Wisla) river basin (Poland): Susudava and Setidava (with a manuscript variant Getidava[63]).[64][65][66] This could have been an “echo” of Burebista’s expansion.[64] It seems like this northern expansion of the Dacian language as far as the Vistula (Polish Wisla) river, lasted until AD 170-180 when Hasdings thrust out from there a Dacian group, according to Shutte (1917), Childe (1930).[67][68] This Dacian group is associated by Shutte (1952) with towns having the specific Dacian language ending 'dava' i.e. Setidava.[69] A previous Dacian presence that ended with the Hasdings arrival is considered by Heather (2010) who says that the Hasdings Vandals “attempted to take control of lands which had previously belonged to a free Dacian group called the Costoboci” [70] On the northern slopes of the Carpathians there were mentioned several tribes that are generally considered Thraco-Dacian, i.e. Arsietae (Upper Vistula) [71][72][73][74][75], Biessi / Biessoi[74][72][76][77] and Piengitai.[72][75] Shutte (1952) associated the Dacian tribe of Arsietae with the Arsonion town.[71] And, the ancient documents attest names with the Dacian name ending -dava 'town' in the Balto-Slavic territory, in the country of Arsietae tribe, at the sources of the Vistula river.[78] The Biessi inhabited the foothills of the 'Carpathian Mountains,' which on Ptolemy's map are located on the headwaters of the Dnister and Sian Rivers (right-bank Carpathian tributary of the Vistula river).[79] Biessi (Biessoi) probably have left their name to the mountain chain of Bieskides, that continues the small Carpathian Mountains towards the north (Shutte 1952).[71] Ptolemy of Alexandria, maintained that the Vistula divided Germania from Sarmatia. Along its northern stretch he located the Gyrhones as well as other people including some Osioi (=Ostoi?) .[80] Ptolemy (140 AD) lists only Germanic or Balto-Slavic tribes, and no Dacians, on both sides of the Vistula (ref: II.10; III.7), as does the Barrington Atlas (map 19)[Full citation needed]

After the Marcomannic Wars (166-180 AD), Dacian groups from outside Roman Dacia had been set in motion. So were the 12,000 Dacians 'from the neighbourhood of Roman Dacia sent away from their own country'. Their native country could have been the Upper Tisza region but some other places cannot be excluded.[81]

South of the Danube, Dacian, in the form of its Moesian dialect, was spoken in the eastern part of the Roman province of Moesia Superior (i.e. eastern Serbia), and in Moesia Inferior (northern Bulgaria), which included the region of Scythia Minor (Rom. Dobrogea).[5]

This section below relies on

references to primary sources or sources affiliated with the subject. Please add more appropriate

citations from

reliable sources.

(June 2011)

During the Roman imperial era, the Dacian language was spoken, North of the Danube, in the ancient region of Dacia, defined by Ptolemy as the area contained by the river Ister (Danube) to the South, the river Thibiscum (Timiş) to the W., the northern Carpathian mountains to the N. and the river Hierasus (Siret) to the E.[82][original research?] Many scholars

There is evidence that Dacian was also spoken beyond Dacia and Moesia. To the West, the zone of Dacian speech probably extended as far as, roughly, the western border of modern Romania, on the basis of a number of Dacian placenames (most of which, however, are difficult to locate with precision).[83][Full citation needed]

To the East, beyond the Siret, it has been argued by numerous Romanian scholars, on the basis of 4 placenames in Ptolemy, that Dacian was also the language of the modern regions of Moldavia and Bessarabia, as far East as the river Dniester. However, numerous non-Dacian peoples, (Sarmatians, Bastarnae and Anartes), are attested in the ancient sources as inhabiting this region[84][Full citation needed] and thus its linguistic status remains uncertain.[Full citation needed]

But the hypothesis of Dacian speakers in eastern Poland is not widely supported among modern scholars, as this region is generally regarded as inhabited predominantly by Germanic tribes during the Roman imperial era i.e. Heather (2009).[85][Full citation needed]

[edit] Dacian vocabulary

[edit] Settlements and fortresses

[edit] Dava element

Onomastic range of the Dacian towns with the dava ending, covering Dacia, Moesia, Thrace and Dalmatia

Ptolemy gives a list of 43 names of towns in Dacia, out of which arguably 33 were of Dacian origin. Most of the latter included the added suffix ‘dava’ (meaning settlement, village) But, other Dacian names from his list lack the suffix (e.g. Zarmisegethusa regia = Zermizirga) In addition, nine other names of Dacian origin seem to have been latinised.[86]

The Dacian linguistic area is characterized mainly with composite names ending in -dava (-deva, -daua, -daba, etc.) ‘a town’. The settlement names ending in -dava, -deva, are geographically grouped as follows:

1. In Dacia: Acidava, Argedava, Argidava, Buridava, Cumidava, Dokidaua, Karsidaua, Klepidaua, Markodaua, Netindaua, Patridaua, Pelendova, *Perburidava, Petrodaua, Piroboridaua, Rhamidaua, Rusidava, Sacidaba, Sangidaua, Setidava, Singidaua, Sykidaba, Tamasidaua, Utidaua, Zargidaua, Ziridava, Zucidaua – 26 names altogether.

2. In Lower Moesia (the present Northern Bulgaria) and Scythia Minor (Dobruja): Aedabe, *Buteridava, *Giridava, Dausdavua, Kapidaua, Murideba, Sacidava, Scaidava (Skedeba), Sagadava, Sukidaua (Sucidava) – 10 names in total.

3. In Upper Moesia (the present districts of Nish, Sofia, and partly Kjustendil): Aiadaba, Bregedaba, Danedebai, Desudaba, Itadeba, Kuimedaba, Zisnudeba – 7 names in total.

4. Besides these regions, similar village names are found in three other places: Thermi-daua (Ptolemy), a town in Dalmatia. A Grecized form of *Germidava. This settlement was probably found by immigrants from Dacia.

Gil-doba – a village in Thrace, of unknown location.

Pulpu-deva in Thrace - today Plovdiv in Bulgaria

[edit] Settlements with irregular names

This section requires

expansion.

There are a number of Dacian settlements which don't have the usual -dava, -deva or -daba ending. Some of them include: Acmonia, Aizis, Amutria, Apulon, Arcina, Arcobadara, Arutela, Berzobis, Brucla, Diacum, Dierna, Dinogetia, Drobeta, Egeta, Genucla, Malva (Romula), Napoca, Oescus, Patruissa, Pinon, Potaissa, Ratiaria, Sarmizegetusa, Tapae, Tibiscum, Tirista, Tsierna, Tyrida, Zaldapa, Zeugma and Zurobara.

[edit] Tribal names

In the case of Ptolemy's Dacia, the tribal names include mostly names similar to those from the list of civitates and very few others.[87] Georgiev counts the Triballi, the Moesians and the Dardanians as Daco-Moesians.[88][89]

[edit] Names of kings and leaders

This section is empty.

This section is empty. You can help by

adding to it.

[edit] Plant names

This section requires

expansion.

Playlisturile mele

Playlisturile mele